Member Spotlight: Bomi Yook

Member Spotlight NewsOlivia Sherman

Who are you and where are you located?

Bomi Yook

My name is Bomi Yook. I'm a media artist based in Calgary, AB, Canada.

Olivia Sherman

What brought you to Canada?

Bomi Yook

Well, I just recently moved back to my hometown where I grew up in Calgary after living in Los Angeles for the past 2 1/2 years, getting my MFA at UCLA.

But I grew up in Calgary. My family moved here when I was in 4th grade. I spent a good deal of my childhood in South Korea and growing up in Canada. So a lot of my work is about that- ideas of hybridity within identity, cultural landscapes, and knowledge systems. I'm often thinking about the history and collective memory of the Korean diaspora with its more complex ties to immigration and colonization.

Olivia Sherman

Interesting. So, what brought you to the New Media Caucus?

Bomi Yook

I knew the New Media Caucus from art school. It’s known among colleagues as a critical and creative community around media arts that isn't just defined by tool sets or aesthetics but focusing more on inquiry. I think it's a space where artists can really bring questions around politics, philosophy, culture, and explore them through digital practice. This hybrid mix of critical thought and new media, felt like home to me.

Olivia Sherman

So what does new media mean to you?

Bomi Yook

That definition is funny, because I think there is nothing new about new media at all. I think as long as there has been a media for expression in art and culture, there has been a form of new media, whether it's the first, you know, daguerreotype in photography or a fashionable technique in painting. The term is always changing with the development of visual and material culture. Currently, AI is considered new media. But before, new media was TV and now TV is just media, you know. The term new media is always shifting. It's always changing a little bit. So I think that's why there's no concrete “this is new media”. That's why I think that shiftiness is a more accurate definition of new media. And because it is shifting and it is shifting with Us, new media is a mirrored study of human history. The human experience as mediated subjects and our relationship to the larger systems of language, culture, ideology, and technology that very much mediate our experience of existence.

Olivia Sherman

I like that. So, what led to the development of your style and use of new media rather than more traditional media like painting or?

Bomi Yook

Again, I think the two terms are not so easily separated [new media and traditional media] because, for someone like me who started out in painting and ended up in computational video art, I still explore painterly sensibilities to image making within the digital space, and I'm still thinking about the history of paintings and image making traditions in the computational work that I do. In that sense, traditional media is always already haunting new media in such a way that a lot of the time it's Not so easy to say that new media is its own thing.

My shift from painting to new media happened when I first learned to code during undergrad at Alberta University of the Arts. Using code to make an image, a moving image, an interactive image felt like solving a puzzle and I liked the complexity about that process and the possibilities that it opened up for what I could make. I like that the way I get to externalize a figment of my imagination into a thing, an image in the world, is by solving this very logical puzzle of code in front of me.

I guess I took comfort in that logic. But at the same time, such order and control comes with an oppressive price. First of all, making becomes super abstracted and there's a separating distance that comes between the artist and the blank page and that thing is computation. So you're one level removed from the immediate, and instead having to solve this very logical almost unrelated problem, which is frustrating. Sometimes I just want to go and put a mark down on a piece of paper, you know? But I can't because I have to code the algorithmic processes by which potential marks could be made by a robotic arm on a piece of paper etc it's exhausting!

I guess that’s where the difference lies between New and Traditional Media for me. New Media has a more abstracted approach to making than its predecessors, often totalizing entire processes of creative gestures in itself, like the robotic arm that can draw with a pencil from different angles. It becomes more about the process- understanding it, capturing it, recreating it, reapplying it. So I think New Media is inevitably a little more meta than the media that came before, it is more self-aware of its own function and processes as a media that mediates something.

Olivia Sherman

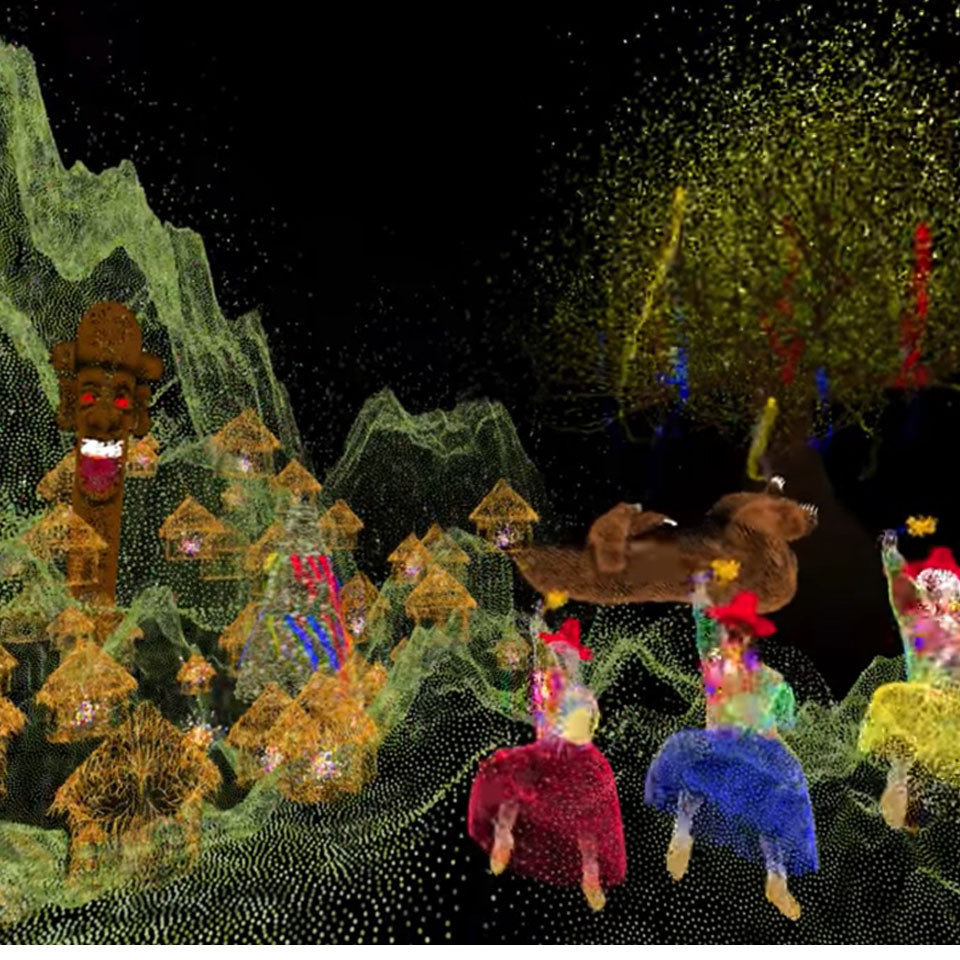

The project that you submitted, K-COSMOSIS, do you want to talk a little bit about that? Is it personal to you specifically? Does it represent your experiences alone, or is it a more universal thing?

Bomi Yook

I think it's both. The project began with a personal experience of my grandmother's funeral as a site of ideological tension. Each relative, depending on their spiritual or ideological leanings, proposed a different way of commemorating grandmother’s life: one rooted in Buddhist and shamanic tradition, another strictly Christian, and another shaped by pragmatic, secular worldview of predominant capitalism. These differing worldviews tried to assert themselves as the dominant logic for remembering someone we all loved. This experience really laid bare how belief systems mediate how we relate to each other, how we remember each other, and how we make meaning together.

This moment pushed me to look beyond the immediate conflict and I began tracing the longer histories of spiritual belief in Korea. And what I found was not a series of separate, distinct, or linear traditions, but a very entangled, messy web of animistic/ shamanic practices, Buddhist rituals, Confucian order, Christian values, capitalistic rationalities have all become adapted into each other, opposing and absorbing one another.

K-COSMOSIS came out of my personal need to hold space for these contradictions within my own identity and not to resolve them, but to reveal how meaning is always being shaped through tension, relation, and proximity to the other. So the project is a personal understanding of my own situatedness within these larger systems of cultural ideological beliefs, but it is still addressing those larger contexts as a broader reflection of the relational and intercontextual nature of belief, memory, and identity itself. I hope that the work resonates with anyone who is navigating conflicting belief systems, fractured cultural identities, or inherited histories that do not reconcile easily.

Olivia Sherman

Something that I really liked about the piece was the audio. What was the process or the inspiration for the audio?

Bomi Yook

The audio was developed to reflect the spiritual and ideological lineages represented in the animation. I mixed sounds from different ritual practices- including Buddhist chants, shamanic percussion and vocals, Confucian ceremonial instruments, and Christian sermons—the soundscape is woven to correspond with each cosmological scene in the work. Rather than keeping these traditions separate, the sounds blend and overlap, shifting gradually from one to another. I treated the audio as a kind of evolving atmosphere—where belief systems echo, interrupt, and transform each other. The goal was to create a soundscape that feels immersive and unstable, much like the themes of entanglement, hybridity, and shared memory that run throughout the work.

Olivia Sherman

Do you have any current projects that you're working on that you want to share with us?

Bomi Yook

I do. Last year, I received a Canada Council Grant to travel to Korea, to research and reconstruct my grandfather’s lost biography as a trafficked laborer in a Japanese imperial coal mine. To research this history, I’ve collaborated with archives and activist groups, like the War and Women’s Human Rights Museum, the Justice Memory Solidarity Foundation Network, the National Museum of Forced Mobilization History, and the Civilian Museum of Japanese Colonial History. This collaborative body of research reveals the systematic brutality of Japanese colonization, including human trafficking, forced labor, sexual slavery, land seizure and resource extraction, famine and displacement, cultural and linguistic subjugation, biochemical experimentation, and forced military conscription.

The Creative Synthesis of this collaborative research is split into two parts based on the archival materials provided to me by Korean archives. So first they provided photographic documentation which I’m hoping will be reinterpreted into a hanging photo-installation. In this I’m exploring an experimental image-making technique I call Split Photography–where images are sliced, interlaced, missing, and cut together and apart- to evoke this sense of rupture and discontinuity that’s inherent in traumatic memory. Creating a kind of impossible image that disables viewers from grasping the entirety of an image and experiencing it as a whole. So Viewers have to navigate indirectly—through fragments of visible moments that emerge between the gaps— exploring identity as centered around a fundamental split.

Secondly, I was provided testimonial sketches hand-drawn from personal memory by survivors of forced labor camps and “comfort women” (a euphemism for women trafficked into violent sexual slavery for the Japanese military). I found these drawings to be very provocative and truthful, as they reveal the violence and horror that were deliberately erased from the archives by the Japanese government after the war in an effort to remove the trace of their imperial aggression and responsibility for wartime atrocities. These personal sketches are currently being reimagined into an experimental animation that examines the violent legacy of Japanese colonialism in intergenerational memory of the Korean Diaspora

I’m developing this work through a series of residencies where I have community support to do so: including the Banff Centre, the Ionion Center for Arts and Culture in Greece, Daimon, and La Bande.

Today, this history remains highly contested, as the Japanese government continues to deny its legitimacy, actively lobbying to obscure it from public awareness by excluding it from educational curricula, national archives, and by reframing it for Western audiences in ways that portray Japan as innocent. In my practice, Poetic archivalship is used as a tool to uncover, process, and cope with colonial history. For me it’s a way to question how art can help metabolize the traumatic past and mediate difficult memories to the public in a manner that is accessible and emotionally resonant. And how Decolonial perspectives can take center stage when narrating the traumatic past of Colonialism.

Olivia Sherman

Do you have a website or anything that I can link in the interview so people can see your work?

Bomi Yook

Yeah. I need to update it, but it’s https://www.bomiyook.ca/